Swedish Design

We made it: up the M50, through the road works, past misleading signs and into the car park. We tied an orange scarf around the front mirror just inside the window so we’d find our silver car again in amongst a sea of silver cars. I’d resisted for so long but was persuaded that today was the perfect day for a gander in Dublin’s first IKEA store. A warehouse of strong colour and hip design that snaked around for miles through every room in the house you could possibly need furniture for. It was full of crying babies, bored husbands, harassed wives, irritated children, and me with my bad back. We touched everything, ran our hands across wooden tables, stroked cushions and bedspreads, opened jars, unzipped bags, poked mattresses, sat on chairs (I nearly didn’t get up again), opened drawers, peered in cupboards, measured, weighed up the pros and cons, wrote notes, exclaimed, admired, resisted and finally, left. It was exhausting! I spent a total of €7.67. My daughter went mad altogether and spent €23.45!

IKEA was founded in 1943 by Ingvar Kamprad. Kamprad probably drew his inspiration from Carl Larsson, another Swedish designer, born nearly a centuary before. Larsson was an artist who began his career illustrating books, magazines and newspapers. He married fellow artist, Karin Bergöö, and together they had eight children and created what seemed like an idyllic life. It was through being

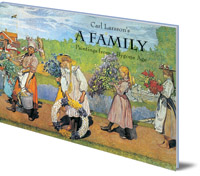

IKEA was founded in 1943 by Ingvar Kamprad. Kamprad probably drew his inspiration from Carl Larsson, another Swedish designer, born nearly a centuary before. Larsson was an artist who began his career illustrating books, magazines and newspapers. He married fellow artist, Karin Bergöö, and together they had eight children and created what seemed like an idyllic life. It was through being  a husband and a parent that Larsson blossomed as an artist and this was reflected in their home, a place where thousands of tourists visit every year. His illustrated books A Home and A Family are still an inspiration to aficiandos of his work.

a husband and a parent that Larsson blossomed as an artist and this was reflected in their home, a place where thousands of tourists visit every year. His illustrated books A Home and A Family are still an inspiration to aficiandos of his work.

Larsson’s major work, Midvinterblot, a huge oil painting that had been commissioned for a wall in the National Museum in Stockholm was rejected on completion by the board of the museum in 1915. Larsson was devastated. The picture, having been offered free to the museum at one stage, was eventually sold to Hiroshi Ishizuka, a Japanese collector. Ishizuka was persuaded, by public demand, to sell Midvinterblot, back to the museum in 1997 where it now hangs, pride of place, in its originally intended destination.

I have, as my desktop picture, a copy of The Kitchen, a watercolour painted by Larsson in 1898. I remember it from when I was a child; I loved its simplicity and wanted a kitchen like that in my home. The picture shows two girls, Larsson’s daughters, churning butter in the middle of a bright and airy room filled with colour: a red chair, the Aga in the corner, a green chest of drawers, an elegant jug, a shelf with curves beneath on which to balance.

Today, in IKEA, I saw the hand of Larsson in each simple yet functional design. It had been done before, over one hundred years ago, yet we all thought it was exciting and new and couldn’t wait to belt up the M50 – recession or not – to create our own flat pack ultra modern lives. Take a bow, Carl Larsson, your work lives on in more ways than you’d have ever imagined!

IKEA was founded in 1943 by Ingvar Kamprad. Kamprad probably drew his inspiration from Carl Larsson, another Swedish designer, born nearly a centuary before. Larsson was an artist who began his career illustrating books, magazines and newspapers. He married fellow artist, Karin Bergöö, and together they had eight children and created what seemed like an idyllic life. It was through being

IKEA was founded in 1943 by Ingvar Kamprad. Kamprad probably drew his inspiration from Carl Larsson, another Swedish designer, born nearly a centuary before. Larsson was an artist who began his career illustrating books, magazines and newspapers. He married fellow artist, Karin Bergöö, and together they had eight children and created what seemed like an idyllic life. It was through being  a husband and a parent that Larsson blossomed as an artist and this was reflected in their home, a place where thousands of tourists visit every year. His illustrated books A Home and A Family are still an inspiration to aficiandos of his work.

a husband and a parent that Larsson blossomed as an artist and this was reflected in their home, a place where thousands of tourists visit every year. His illustrated books A Home and A Family are still an inspiration to aficiandos of his work.Larsson’s major work, Midvinterblot, a huge oil painting that had been commissioned for a wall in the National Museum in Stockholm was rejected on completion by the board of the museum in 1915. Larsson was devastated. The picture, having been offered free to the museum at one stage, was eventually sold to Hiroshi Ishizuka, a Japanese collector. Ishizuka was persuaded, by public demand, to sell Midvinterblot, back to the museum in 1997 where it now hangs, pride of place, in its originally intended destination.

I have, as my desktop picture, a copy of The Kitchen, a watercolour painted by Larsson in 1898. I remember it from when I was a child; I loved its simplicity and wanted a kitchen like that in my home. The picture shows two girls, Larsson’s daughters, churning butter in the middle of a bright and airy room filled with colour: a red chair, the Aga in the corner, a green chest of drawers, an elegant jug, a shelf with curves beneath on which to balance.

Today, in IKEA, I saw the hand of Larsson in each simple yet functional design. It had been done before, over one hundred years ago, yet we all thought it was exciting and new and couldn’t wait to belt up the M50 – recession or not – to create our own flat pack ultra modern lives. Take a bow, Carl Larsson, your work lives on in more ways than you’d have ever imagined!

Labels: art, Carl Larsson, IKEA, M50